Ratings Systems

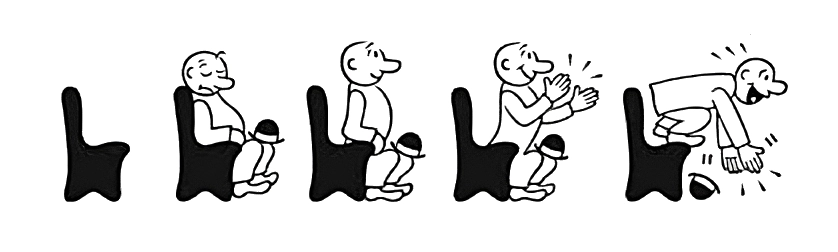

The SF Chronicle Little Man from this article; cropped, resized, and compressed with ezgif.

Ratings systems in media criticism are fascinating. They sit at the crossroads of design, communication, and data modeling. Their goal is tremendous: to bridge a gap from a reviewer's subjective sentiment to a reader's subjective expectations.

These systems are necessarily visual. The tension between the visual representation and the data they convey leads to two design philosophies: top-down, and bottom-up. You can either start with a desired visual representation and force your data into that scheme, or you can start with the data and let a visual representation emerge.

The chosen design constructs a space within which interesting edge cases can be expressed. Are half-points allowed? What about one-off values and symbols? What about zero scores, or empty ratings? Does a lack of rating itself indicate something?

In this brief survey I'll touch on the most common rating systems used in media criticism, then highlight some unique designs that have been highly influential. Along the way I'll point out some of the edge cases and the ways critics have grappled with the design constraints of their systems.

Numerology

Some of the most common systems are based on numbers. Almost always they are one of these values:

- 2 – Thumbs up or down; a single indicator like a heart, asterisk, or star which is either present or absent.

- 3 – Bronze/Silver/Gold; contemporary Netflix thumb ratings with a two-thumbs up option; some star-rating systems.

- 4 & 5 – ABCDF; Very common for star ratings.

- 10 – Five stars with half-stars; a number-out-of-ten

- 100 – Percentage; a number-out-of-one-hundred; a number-out-of-ten with one decimal place.

All of these have room for some shared edge cases. Sometimes zeros are allowed, and sometimes they aren't. Some allow custom values, or breaking beyond the maximum, for very rare occasions. Many times exclusion is itself a rating, representing a less-that-zero ultimate snub.

Sometimes, if the system is too coarse, absence of a rating might represent a neutral sentiment. How many times have you intentionally not rated something on Netflix because you didn't want to nudge the algorithm in either direction?

Astrology

Stars were mentioned many times above but they deserve a special call-out. Star-based ratings are so diverse and omnipresent they have their own wikipedia article, and it's quite the read.

The article elaborates on the thorny issue of zero rankings:

Critics have different ways of denoting the lowest rating when this is a "zero". Some such as Peter Travers display empty stars. Jonathan Rosenbaum and Dave Kehr use a round black dot. Leslie Halliwell uses a blank space. The Globe and Mail uses a "0", or as their former film critic dubbed it, the "death doughnut". Roger Ebert used a thumbs-down symbol. Other critics use a black dot.

You'll see the article highlights many of the edge cases I mentioned, and more. The prestigious Michelin stars are a prominent example, where an affirmative ranking of zero stars is not a snub. Being mentioned at all is intended to be an honor. (I hate it.)

You may also notice Leonard Maltin's system. It's a 4-star system which permits half-stars, except that a rating of exactly one half-star is not allowed, resulting in 7 possible ranks. The lowest rating of a full star is replaced with all-caps "BOMB." How bizarre.

Symbology

Some rating systems break the mold so significantly that the systems themselves capture the imagination. These four examples below made a particularly lasting impression.

Famitsu

This Japanese gaming magazine famously scores video games on a 40-point scale by having 4 judges each contribute a rating out of 10 and adding their scores together. At time of writing, in over 25 years this system has only produced 28 perfect scores.

I find this system particularly fascinating in the context of this post because it blends bottom-up and top-down design. Having each reviewer score games based on a 10-point system is top-down; inorganic. But adding their scores together without averaging them is a bottom-up representation of a score as given by a panel rather than an individual. It's so simple - no symbols, just numbers - yet manages to be one of the most unique among well-known rating systems.

SF Chronicle

Movie reviews in the San Francisco Chronicle have, for many decades, been rated with a unique metric: a small drawing of a man in a movie theater seat reacting to the film. Rodger Ebert famously weighed in:

The only rating system that makes any sense is the Little Man of the San Franciscio [sic] Chronicle, who is seen (1) jumping out of his seat and applauding wildly; (2) sitting up happily and applauding; (3) sitting attentively; (4) asleep in his seat; or (5) gone from his seat.

All 5 Little Man poses. Taken from this article, upscaled with upscale.media, then edited and cropped in GIMP.

The blessing of the Little Man system is that it offers a true middle position, like three on a five-star scale. I curse the Satanic force that dreamed up the four-star scale (at the New York Daily News in 1929, I think). It forces a compromise. So why don't I simply drop the star ratings? As I have explained before. I'd about convinced my editors to drop them circa 1970, when [Gene] Siskel started using them. To drop them now would be unilateral disarmament. Do editors even care about such things? You're damned right they do.

At the end of the article, Ebert hosts a long message from the Chronicle's film critic, Mick LaSalle, who explains the five poses, the editorial guidelines around their usage, and audience feelings about them. It's a great little read. Of topical importance, LaSalle draws comparisons to other rating systems. He mentions that the second-highest rating corresponds to a letter grade better than a B-, and that an A- ambiguously "can go either way" between top two ratings, noting "we don't have the equivalent of a three and a half star rating."

Christgau

Robert Christgau is a prolific music critic who wrote books cataloguing his reviews of albums from the 70s, 80s, and 90s which were later archived on this garish website. He used a harsh letter grade system as his core, and permitted leaving no grade at all. He expanded his system to include the following additions which he sometimes mixes and matches:

- One to three asterisks for degrees of honorable mention based on the reader's attunement to a genre or aesthetic.

- A scissors icon calls out a good song on a bad album.

- A bomb icon for a particularly bad album.

- A turkey icon for a bad album that's otherwise notable.

Fantano

Anthony Fantano is a Lemonhead mascot popular music critic on YouTube who uses a 10-point system with several augmentations:

- 0 is permitted and is meant to be offensive.

- Some albums are given a "NOT GOOD" rating instead of a number.

- Scores can be ranges rather than single numbers.

- Scores can be modified by adjectives "light", "decent", and "strong" which can also be used as ranges.

- Often with ranged scores, only one score is visually displayed. Some take this to indicate which is the "real" score within the range.

A glorious anon took the time to record over 50 of his reviews with high fidelity. Scores like "Strong 8 to [Light 9]" and "[Light] to Decent 4" are peak Fantanocore.

Signing Off

This strange topic has become a bit of an obsession for me. I'm a collector, now. If you happen to know of other ornate rating systems or other writings on the topic, I'd love to hear about it. I'm feeling a light to decent thanks in advance.